Men’s Golf Senior Jake Maples Embraces Adversity

Georgia Southern hosts the Schenkel Invitational March 19-21.

Marc Gignac

3/18/2021

STATESBORO – Adversity has never obstructed men’s golf fifth-year senior Jake Maples. He has always found a way through or around hardship and summoned the strength to move forward.

Stoic but brimming with confidence, he has heard words like “no” and “can’t” more times than he cares to remember, and his physical response tends to be a shrug of the shoulders and maybe a wry smile. There might be a comment, dripping with his dry wit and sarcasm. But make no mistake, a fire will have been ignited, and it will drive him to work and ultimately prosper.

The drive comes from literally a lifetime of beating the odds and overcoming adversity.

“He has that part in his heart that tells him, hey, ‘I'm going to do this and I'm going to be successful,’ because he has overcome and does dig deep when it comes time to dig deep,” says Carla Maples, his mother, and she ought to know.

Babies are born with a hole between the left and right atria (upper chambers) of the heart that usually closes naturally. During his first visit after coming home from the hospital, Jake’s pediatrician discovered his had not closed yet. Technically referred to as a patent foramen ovale, his doctors decided to continue to monitor it, still thinking it would heal on its own.

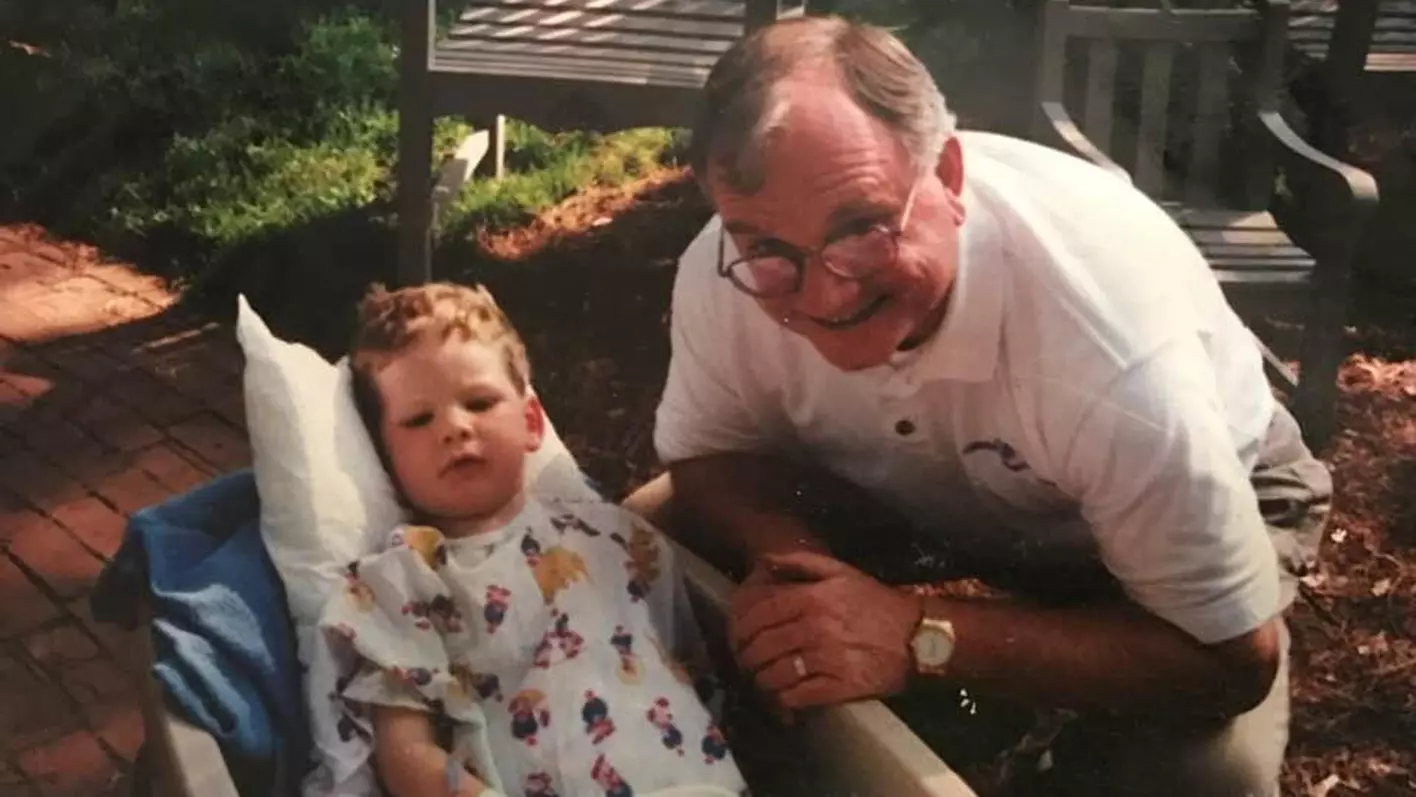

Jake saw his pediatric cardiologist every three months, and in March of 2000, when he was 2-and-a-half, the doctor diagnosed him with atrial septal defect, and the decision was made that the best thing for Jake would be open-heart surgery to repair the hole. Carla and Jake’s father, Robbie, were, as she says, “scared to death about it.”

“Her only child was going in to have his heart repaired and going to be put on a heart-lung machine,” says Jake, who does not have much recollection of the event. “I can imagine how scared she was.”

Surgery was scheduled for May 10 at Egleston Hospital in Atlanta, a 50-mile drive from their home in McDonough, Georgia, but doctors advised Carla and Robbie not to tell Jake because it would scare him.

“We told him we were going to the doctor, and of course, he was great,” remembers Carla. “He's riding around in his little wagon that they have at Egleston that you see lots of kids in.”

The normal procedure for open-heart surgery is to lower the patient’s body temperature to where the heart is barely beating and put the patient on an ECMO machine, which essentially adds oxygen to one’s blood and pumps it through the body like the heart.

Carla and Robbie said goodbye to their first-born son and only child as he was wheeled in for surgery. They received regular updates and after what seemed like an eternity, the doctor came to talk to him.

“I just remember our pastor leaning over me and Robbie,” says Carla. “It was just the three of us standing with the doctor - and he said, 'how long was he on the ECMO?' For whatever reason, that bothered our pastor. And he (the doctor) said, ‘I never turned it on. His heart was strong enough that it quivered, and I operated on it and fixed it while it was quivering.’ So we love that story. We love that he never had to have that turned on, that his heart has always been strong. He's always been a strong person.”

Jake recovered well and had no physical restrictions growing up. He began playing sports as early as age 3. He played football, baseball, tennis and golf as a youth, but his passion was on the diamond. Robbie had played a lot of baseball growing up and passed on his love of the game to Jake. Baseball was what Jake wanted to do.

He proved to be very talented on the mound and threw in the low 80s when he was 14-years-old. It looked like he would have a bright future in baseball. It was in the fall of his freshman year at Union Grove High School when adversity struck again.

“It was like kind of over time, my elbow was achy,” says Jake. “It hurt to just have it hanging by my side.”

Jake hoped rest and recovery would solve the problem, but instead, it got progressively worse. He went to see Dr. Andrews in Birmingham and after an MRI, they found three stress fractures in his elbow.

“I had to go in a cast for six or eight weeks, and they told me even when I come out of the cast, I wasn't going to pitch again, like I would never throw a baseball as hard as I could again,” says Jake matter of factly.

Robbie and Carla were devastated. With him being their only child, his playing baseball had become as much a part of them as it had Jake himself.

“When baseball happened, we were totally heartbroken,” Carla recalls. “Jake - we don't know where he gets it; we think he gets it from God - because we were still - I couldn't talk about it without tearing up because we knew he was going to go big places with that. If you ask people around now, they will still comment about his baseball.”

If Jake was upset, he did not show it, at least not visibly. He simply moved on to a sport that would not make his elbow hurt. He looks back on it now with a little more perspective.

“If it would have happened at like where I am now, it probably would have been more devastating, but I was pretty young and immature and just wanted to play sports,” he says.

He turned his attention to golf because as Jake puts it, “golf and baseball go hand-in-hand as weird as that sounds. I don't really know the physics of it, but they do.”

He had played four or five times a year with his father and grandfather growing up, but now, he wanted to get serious about it. High school golf tryouts were in January, and his elbow felt good enough to give it a shot. His doctor gave him the green light.

“I decided that this is probably my second-best sport, like my only second sport that I really played so I decided just go to golf tryouts,” says Jake with a chuckle. “I made the team somehow. I don't know how. I wasn't any good.”

Jake redirected the passion he had for baseball into golf. Every day after school, he went to play a round or at least spend some time at the driving range or practice area. He started playing junior tournaments the summer after his freshman year of high school and began playing with Rusty Strawn, a Georgia Southern alum, who helped grow his game.

“I decided that this is probably my second-best sport, like my only second sport that I really played so I decided just go to golf tryouts. I made the team somehow. I don't know how. I wasn't any good.”Jake Maples

“I was hooked,” he says. “I just wanted to get good.”

Jake wanted to keep playing at the collegiate level, but he had gotten a late start and needed more experience, especially on the junior circuit. Some NAIA schools showed interest, but that was pretty much it. There were no scholarship offers.

“To put it frank, I wasn't good enough,” Jake says. “I don't blame them for not taking me because I probably wouldn't have taken me either.”

Dave Jennings, the head coach at Central Alabama Community College, heard about Jake from a former player who lived in McDonough and offered him a spot on the team. Jake was named a Freshman All-American in his first season and ranked as high as eighth in the NJCAA Golfstat rankings in his second season, but as the fall semester came and went, the Division I offers still did not come. That’s when Georgia Southern and Carter Collins got involved.

Strawn reached out to Collins about Jake, and Collins reached out to Jennings, who has had a couple former players sign with Georgia Southern. Jake had already familiarized himself with the Georgia Southern program, and after a deeper dive, it became clear this is where he wanted to be. A visit was orchestrated near Thanksgiving, and Collins, who had seen all his results, told Jake the last step was to see him play. Jake was set to compete in the Jones Cup Qualifier at Sea Island in December.

Collins had thoroughly done his homework prior to the event and says he saw Jake hit one wedge on the driving range and knew he was going to offer him.

“I just needed to see that it wasn't fluke,” says Collins. “That all those scores were legit, that everything I had been hearing about this guy was legit. He had really good mechanics for a 50-yard wedge shot that looked great, and it just clicked. It felt right.”

The trouble was that Jake didn’t know that. On the 13th hole, about five holes into his round, he hit his tee shot out of bounds, and Collins, who was watching from just off the fairway, was the one signaling the ball was out of bounds. Jake teed it up again and put it in the same spot, literally about a foot from his first ball, out of bounds.

By the time Jake made it down the fairway, Collins had left to go look at other kids he was recruiting.

“He hit two balls out of bounds and saw us walk off, so he assumed we were done recruiting him, but it couldn't have been further from the truth,” says Collins.

“So we're walking down there - and the hole is higher than the path at the time - and Jake looks over at me and he goes, ‘Mom, you better call Rickett,’ because Ben Rickett is the coach at Dalton State and they had been looking at Jake,” Carla recalls with a smile. “He was thinking there is no way Carter Collins is going to take me.”

“I shot 80 that day,” says Jake. “I wasn't nervous; I just didn't play good. I was fully not expecting him to call me whenever he did and offer me but thank God he did.”

Collins called that night and offered him a scholarship.

“He did sound a little surprised, which was surprising to me, but looking back at his side of the story, I understand where his head was at the time,” Collins says with a laugh.

“I shot 80 that day. I wasn't nervous; I just didn't play good. I was fully not expecting him to call me whenever he did and offer me but thank God he did.”Jake Maples

The end of the call went something like this.

Carter: We want you to be a part of our program if this is a place that you want to be.

Jake: Yes, I accept!

Carter: Well, I tell every guy the same thing. Just sleep on it and talk to your parents a little more. Let them know everything that's going on so that we're all on the same page, so we know that you're in, when you're in.

Jake: (long pause) Well, I'm gonna have the same answer in the morning.

Carter: (chuckling) Well, I hope so.

Jake: Ok. What time should I call you?

Carter: 9 o’clock.

Next morning at 8:59 a.m., Jake calls: Hey coach.

Carter: Hey Jake.

Jake: I’m still coming.

Carter: (chuckling) Ok. Glad to hear it!

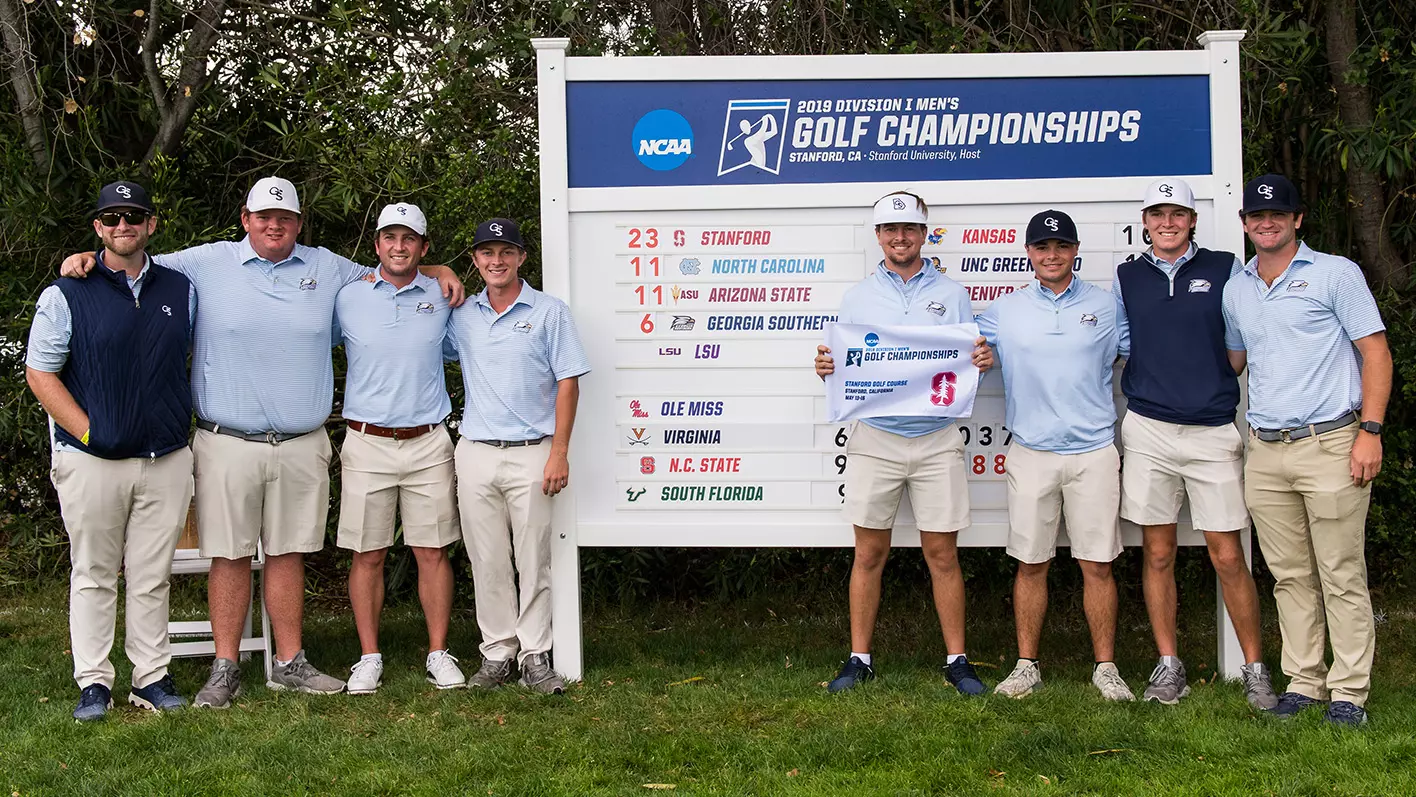

Jake was named third-team All-Sun Belt in his first season at Georgia Southern and enters the 41st playing of the Schenkel Invitational, the Eagles’ home tournament, with seven top-10 finishes, including three top-5s and a win.

“To me, it's an incredible story of perseverance,” says Collins. “Like Jake has said before, he's been told ‘no’ a lot in his life. Baseball career is up and coming and it looks like he's going to have a bright future in that, and all of the sudden he injures his elbow, and 'No, you can't play baseball anymore. You have to find a new future.' That's a really hard thing for a young high schooler to hear. Then he starts with golf, and he starts thinking about playing college golf and he's told, ‘No, there's no future for you in college golf.’

“From not playing high school golf middle way through high school to being a first-team JUCO All-American his sophomore year, really a four or five-year span, is incredible. That's somebody who really took advantage of somebody telling them ‘yes.’”

Jake and his Eagle teammates saw their 2019-20 season end during the practice round of the Schenkel Invitational because of COVID-19 just over a year ago. He was unsure at the time if the NCAA would grant another year of eligibility that would allow him to come back as a fifth-year senior. He would later write in an article for GSEagles.com, “It might’ve been the most lost I’ve ever felt. I had no clue what was next. I thought for sure that I had put a Georgia Southern golf bag on my back for the last time.”

He is relishing this mulligan.

“The relationship I've made with coach and these guys is unreal,” he says. “As far as what else do I want to do - win a tournament, win conference, go back to regionals. That was probably the most fun I've ever had on a golf trip. Oh, my gosh. That was awesome! Go back to regionals, go back to nationals, make some noise at nationals, win nationals. That's about it.”

When the college season ends, Jake, who will be getting married to fiancé Madison in September, plans to turn pro and live on St. Simons Island.

“We're going to turn pro and see what happens,” he says. “That's my plan right now. I've got an awesome support system - my parents and the people close to me. If I don't make it, it's going to be okay. We'll go from there, but that's the plan right now. ”

A word to the wise – don’t bet against him.

“It's the same game; it's just for money this time,” he says with a shrug.